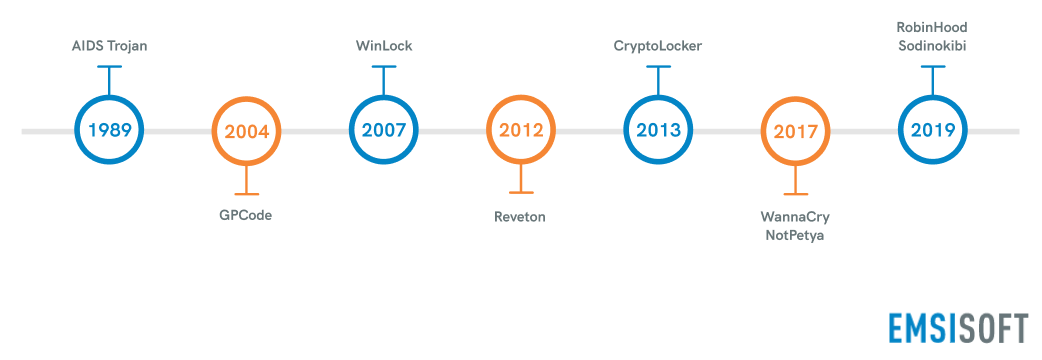

The first documented example of ransomware was the AIDS Trojan, written by Joseph Popp in 1989. Popp, a Harvard-educated evolutionary biologist, distributed 20,000 infected discs to people who had attended a World Health Organization’s AIDS conference. After an infected system had rebooted 90 times, the malware encrypted the names of all files in the C: directory and instructed the user to send $189 to PC Cyborg Corp via a post office box in Panama if they wished to recover their files. However, the decryption key could be easily extracted from the malware, and thus the AIDS Trojan never posed a serious threat. Popp was eventually caught but was declared unfit to stand trial.

For the next 10 years, ransomware remained largely dormant, although researchers speculated it would return and pose a greater threat. They were correct. The proliferation of the Internet in the early 2000s gave cybercriminals an opportunity to monetize ransomware on a large scale and utilize more robust encryption techniques that were far harder to crack than the rudimentary cryptography used in the AIDS Trojan.

The first true example of crypto ransomware, GPcode, arrived in 2004. Primarily targeting Russian businesses, GPcode encrypted files using weak RSA encryption and demanded users pay a ransom via Yandex, a Russian online payment system similar to PayPal.

2007 marked the arrival of the world’s first prolific screen locker, WinLock. Rather than encrypting files, WinLock locked victims out of their devices, displayed pornographic images and instructed users to send a $10 premium-rate SMS to receive an unlock code. WinLock inspired dozens of copycats, many of which masqueraded as legitimate products and used basic scareware tactics to extort victims.

In 2012, Reveton popularized “law enforcement” ransomware, a new take on screen lockers that preyed on people’s fear of authority and made them question their own innocence. Reveton locked users out of their devices and issued an official-looking document that appeared to have been sent from a legitimate law enforcement authority such as the FBI or Interpol. The document claimed that the device had been used for illegal activity and would be locked until the user paid a fine.

In 2013, CryptoLocker was released. CryptoLocker set the new standard for crypto ransomware. Not only did it utilize 2048-bit RSA encryption, but it was also one of the first ransomware variants to be distributed through compromised websites, which were part of the Gameover ZeuS botnet.

In the years that followed, a number of major ransomware outbreaks impacted millions of individuals and businesses around the world, including WannaCry, NotPetya, SamSam and Cerber, among many others.

Toward the end of the 2010s, ransomware groups became more selective with their attacks, shifting their focus from home users to larger targets such as businesses, schools, MSPs and government agencies. As a result, the total number of global ransomware attacks declined, but ransom demands skyrocketed. Ransomware operators also began operating more like professional enterprises, leasing their services to other cybercriminals and providing regular updates to improve their software. At the end of 2019, ransomware groups began stealing data and using it as additional leverage to coerce victims into paying the ransom.